- Home

- Lou Sylvre

Falling Snow on Snow Page 2

Falling Snow on Snow Read online

Page 2

SNOW IN Seattle is often an ephemeral thing, covering the city by night, gone by day. But this time, contrary to predictions, it not only remained but kept falling, creating sledding hills out of residential streets and blocking doorways with drifts. On Friday, the shoppers still came to the Market, and Christmas music proceeded to echo through the halls, including that produced by Beck’s guitar. If anything, the people were a little less hurried, maybe their smiles a bit more genuine, but they still wanted “White Christmas” and “Jingle Bells,” and Beck didn’t think any real goodness resided at the heart of the holiday season, whether white or blue or even rainbow.

The snow stopped Friday afternoon, but started again in the silver dawn Saturday morning, and that day the Market seemed as whisper quiet as the rest of the city. Around four in the afternoon, Beck was performing in one of the Market’s coldest and generally least bustling corners. Of the few people passing by, not one stopped to listen, and Beck’s fingers responded of their own accord by simply stopping. He sat down in the corner, his back against the wall, and looked out a long window opposite. The sun shone momentarily, its isolated orange rays slanting through the falling flakes as if giving a wave to remind the city it still burned. The sight was mesmerizing, and Beck didn’t think at all before he started to play a song he loved—a song of a Christmas day grim and harsh, one which, unlike storefronts and Santa photos, might harbor true compassion.

Beck’s fingers coaxed a dark, cold wind from the strings, and he felt the words of the hymn he played rise in his throat and form on his tongue. He let them loose, speaking them like a poem of loneliness, and left them hanging in the air on frozen breath.

“In the bleak midwinter frosty winds made moan.

Earth was hard as iron, water like a stone.”

He wanted to stop the words. They made the music more beautiful, more true than ever, and he wanted to listen to it, to hear what his hands were telling him. This wasn’t the kind of music to play to a Christmas-shopping crowd at Pike Place Market—he knew that. Yet where moments before no one had even looked at his happy caroling guitar as they passed—even if they tossed money into his open case—now he saw through the screen of his eyelashes that people gathered. They waited for something, a small crowd still as a deep winter night.

Despite his reluctance, his words continued to steal out into the world as if they had every right to his voice, but then he heard something else. At first he thought it an echo—the market was full of them—but it gained in strength and beauty, and he understood. Someone had begun to sing. Clear, brave, flawless as Beneventan chant.

Like an angel in a cathedral.

His own words became a whisper, his fingers grew more sincere as they traveled the strings in pursuit of a beauty that would match the singer’s voice. He lifted his gaze to search the small crowd that had gathered, but not one among the men, women, or children moved their lips or seemed to do anything but listen, perhaps as enchanted as he was by the sounds. It seemed a moment touched by something beyond the mundane, and he thought of his grandmother’s rosary hanging as always around his neck, though it meant nothing religious to him at all.

Beck wasn’t, in fact, a man of religion. And though he admitted the possibility that something more existed than what could be seen, the closest he knew to spirit lived right there, in the music. In the tones born in the body of a fine guitar, the passage of breath through the vein of a flute. In the flight of sound on the wings of a perfect voice. Like this one.

“Snow was falling, snow on snow.” The singer wove the words over and under the harmonies Beck offered up with fingers and strings, turned them into something different, something more.

The song ended, as all songs do. But this time, when the words stopped and the echoes died away, Beck felt a thrill of panic, for he still hadn’t located the person who’d been singing. What if he never found the singer, never again heard that soaring voice, never looked into the eyes of the man who sang. Yes, he thought, a man. He hadn’t been sure at first, as the alto voice had reached notes high for the range. But it’s a man, he thought again, and he knew it because of the way the voice had touched him.

He stood and again scanned the crowd. He asked an older couple standing near, “Did you see who was singing?”

They shook their heads, but the woman smiled gently, as if the soul-deep need he felt could be seen on his face, heard in the phrasing of his question. He tried to smile back.

As quickly as he could, he gently laid his guitar in its case and ran. He rounded the corner of the shop and looked up the long, dimly lit hall that sloped up to the next level of the market. A slender man in jeans, with long, curling hair and loose flannel shirt trailing behind him like a cape, strode quickly away. It’s him!

“Wait!” Beck called, and the man half turned as if to obey, but instead spun back around and kept moving. Away from Beck. He turned a corner at the top and was lost to sight. Beck warred with himself—he wanted to follow and find him, needed to. But he also needed to eat and pay rent. If he followed his heart, the money people had tossed in his guitar case wouldn’t be there when he came back. Nor would his instrument, his livelihood, his only means of staving off damp cold and gnawing hunger. So he turned back, picked up his Seagull, and began a catchy rhythm for “Up on the Housetop.”

He didn’t care about “Up on the Housetop,” and though people were smiling and tossing money in the case, he had never been more certain that Christmas was nothing more than hype and a good sales strategy. “Bah,” he muttered into his instrument. “Humbug.”

Except. Somewhere out there was a man with an angel’s voice.

Gone. Like everyone else. I’ll never see him again.

ALL THOUGHT of going upstairs for coffee fled Oleg’s mind, though that had been the whole reason he’d come through the Market this morning on his way home. He wrapped his smelly shirt close around him and started to run. He felt completely stupid doing it, but he didn’t stop until he was sure he’d lost his pursuer.

What am I running from?

Oleg had no sensible answer. The man with the guitar was just that, a man, and the devil could testify Oleg didn’t usually run from an interested man—especially not one who looked like the guitarist. All long legs and strong hands and s-e-x from head to toe.

Which is what Oleg thought he probably smelled like—sex. He’d “gone out” the previous night. “Out” was where he told his family he was going when he went prowling bars for someone who’d hold him tight, who’d touch him, need him, want him. Someone who’d fuck his brain quiet and satiate the longing he was never free of for long.

The first man he’d picked up last night had only wanted to fuck in the car. The sex was hot and quick, as sex in semipublic places tended to be, but the encounter didn’t even rattle the empty spaces. The second of the night had gone a little better. The man—who said his name was Jim—took him home to a spacious apartment near Broadway and fucked him good for an hour, then fell into a coma-like sleep. Oleg had stayed, though he hadn’t slept much, fantasizing instead that this encounter wasn’t more of the usual, that the man who slept beside him hadn’t simply forgotten to kick him out the door before he fell asleep. But in the morning, Oleg realized—even before Jim showed him the door—that he didn’t even like the guy, with all his cold, sharp-edged décor and heavy gold jewelry.

That, in fact, was the problem with the overnight kind of hookup. If he let them—and he always did—they could seem to sate more than sex drive. In truth the encounter with Jim was no different than the car-fuck, except he had farther to fall back down when it was over. True to form, by the time Seattle’s rare December snow cooled the sex memory off him, Oleg was lonely again.

Lonely.

Most of the time, he didn’t like to think that’s what he was. He was a lucky guy; he knew that. He had a big, loving, accepting family, and all of them had more to be thankful for than many. They’d come from cold, hungry Russia in the 1990s, and unlike most r

efugees they had what were called by the welfare people they’d had to depend on when they first arrived, “marketable skills.”

What the family had was music, and it had opened so many doors for them. Now they had made their name in early music circles, had regular bookings for concerts and special appearances as a group and individually, and they had a home. Warm, large but not so much so that it ever felt too spacious. Never empty. Air rich with the smells of stroganoff, borscht, shashlik, or honeycake. Ready laughter, flashin-the-pan tempers, small favors asked or done. And behind it all, in the Abramov home, always the music: scales ad infinitum, students repeating sixteen measures over and over slow to fast and finally tumbling into the following passage. Sometimes, too, whole beautifully sculpted pieces, perilous to the listening—or performing—heart.

Home, for Oleg Andreyevich Abramov was a luck-laden word indeed, for in Russia, beloved though the country might be in some ways, the family had endured cold and hunger and hate—the former because of political and economic collapse, the latter mostly because Andrei, Oleg’s father, was Jewish. Oleg, youngest by nine years, had only faint memories of the old country. A grandmother sang “Dreidel, Dreidel, Dreidel.” A tiny room held only a bed, where a faded and frayed diamond quilt of velvet, silk, and wool warded Oleg and his brothers against winter. Snowdrifts loomed taller than a little boy. His mother’s hands gamboled over the keys of a scratched piano. His uncle spun him in circles, smelling of bow rosin and lavender.

But distant and dim as those memories might be, they remained very much a part of Oleg, because the Abramovs had brought the old country with them to Seattle. The mild climate had done nothing to dispel the sense that a family huddled tight together would weather any storm.

One might have expected such a family to resent a child—the youngest and all but a straggler—who was different. But when Oleg had told his mother he was gay, she’d accepted it.

“Yes, I believe I already knew,” she said, her gently accented speech conveying as always a love of life’s surprises. “Or at least I should have.” She laughed and hugged him and set the tone of acceptance for the family. It persisted even now, after her death. He remained their Olejka, a precious member of the family.

Yes, his life was full of home—meaning love and warmth and acceptance.

But that didn’t eliminate the longing. Maybe, it changed the shape of the emptiness, made it even harder to fill. Because Oleg wanted more of what he already had. He wanted a man who loved him, who would take him wholesale into his life and also be willing and able to weave himself seamlessly into Oleg’s family.

“You look in the wrong places!” That had been part of his mother’s last words to him.

He’d entered her room where she lay propped on a mound of stark white pillows. She had chosen to fight the pain of her tumors and remain conscious for a last private talk with each of her loved ones.

“Mom,” he’d said, the most American of her offspring, and sat on the edge of her bed, carefully taking her small, bone-thin hand in his. He’d wanted her to embrace him, but knew she didn’t have the strength. He kissed her forehead, and she smiled. As he straightened, she fixed her dark brown, remotely Asian eyes on him and spoke, her voice low, her accent spread thicker than ever over the English words.

“Son, I know what you do, the nights you leave us. I can smell the liquor on you, and yes, the men.”

Alarm shot through him. He’d thought he was circumspect, careful, never coming home drunk or with his clothing too much in disarray. “Mom, I’m sorry—”

She cut him off, momentarily stern. “No need, no time. Listen. What you are finding is not what you are looking for, in your heart. What you are looking for is not easy to find, but also not impossible. But Oleg, you are looking in the wrong places!”

Oleg had wanted to redeem himself in her eyes. “Mom, some really great people hang out at bars, clubs. Nice men. People you’d like.”

“Of course, Olejka,” she said, seeming energized by fond frustration. “But I know you do not go to find friends and conversation. And don’t look so shocked. I am praktichnaya jenchina! Practical woman, yes? Good eyes, smart brain, and I’ve… how do you say it? Been around the corner?”

Oleg had to smile, but in the face of losing his mother, the affection in that expression gave way to grief, and by the time he spoke, he had to push the words through tears. “The block, Mom,” he managed. “You’ve been around the block.”

She stopped speaking then, panting and breaking out in sweat from what must have been a sudden flare of the ever-present pain. After a moment, the spasm seemed to pass, and she fixed her failing gaze on Oleg once more. “You do not go for the friends, my son. It is not easy for you, the talking, the obshcheniye… friendly drink. You go alone. You come home, you are loneliest. Always.”

She closed her eyes. Oleg squeezed her hand gently, sorry for exhausting her. She found the strength to squeeze back but kept her eyes closed as she spoke. “The places are fine, Oleg. But for your looking? They are not… useful.”

Quiet fell between them, lasting exactly eleven of his mother’s breaths—Oleg counted them. When she spoke again, it was only to tell him that he, her youngest, her surprise child, remained always precious to her, and her love would remain with him despite death’s separation.

And then the audience was over. “Send in your sister Lara now, Olejka.”

He thought about her insight now, more than a year since, as he fled down the back stairs of the market and stepped out into the chill weather on traffic-snarled Western Avenue. He wrapped his flannel shirt tight around him and bent his head against the wind as he walked around to Third and Virginia to catch the bus, which would take him home to the Greenwood neighborhood, a place that bore no resemblance to the bars on Broadway at all. He’d be safe there, almost smothered with love, and he wouldn’t have to think about why he was running away from the man with the guitar.

Oleg had enough insight into his own mind and heart to know what his mother had said was true—had known it even before hearing it from her mouth. But the facts remained. He saw the people that went to the bars for simple camaraderie—often couples, sometimes just friends. He didn’t know how to become that, and it wasn’t why he went there. And always—after a few drinks—the hookups, the sloppy kisses and minimalist sex, the indulgent and dangerous self-deceptions all became easy. Today, letting his voice float through the market suspended in the lovely chorded tones of the beautiful man’s guitar had been easy too, natural.

But talking to a man like the guitarist was not.

Now, stinking of last night’s booze and sex times two, wearing the crumpled, sweaty clothes he’d worn through dancing, drinking, and car sex and finally picked up off a stranger’s floor, such a thing as turning around to meet the guitarist wasn’t even possible.

Poorly clad for the weather, he dashed through the snow and met the bus just as it arrived. After flashing his metro pass, he made his way toward the back. Glad to see for once there was a seat available, he swung into it and sat down more heavily than he’d intended.

I’ll probably never see him again.

He closed his eyes on the discouraged, empty way that thought made him feel and let himself drift into a light doze filled with the faint imagined sound of snowfall, and of arpeggios becoming fingers playing lightly through his hair.

He jerked awake just in time for his stop, sure as if he’d set an alarm. Back out in the cold, walking the one-block distance to his house, he wondered if the snow would stay for Christmas.

As soon as he got inside his over-the-garage room at the family home, he pulled the blinds, stripped his smelly clothes, and stepped into a long, hot shower. The difference in the way he felt before and after amazed him, even though he’d been through precisely this transformation dozens of times before. Shaved and combed, dressed now in clothes that were much the same as what he’d worn before but clean and soft and not at all grungy, he smiled forgiveness at himself

in the mirror.

He stepped out into the weather once more for the twenty steps it took to get to the back door of the house, then slipped inside to the homey warmth of the kitchen, where Lara was heating water for tea. When she turned to greet him, he saw inconvenient knowledge in her eyes, accompanied by fathomless compassion. She set down the worn dish towel she’d been drying her hands with and drew him into a hug. Suddenly Oleg’s heart felt heavy as stone. He clung to her, this older sister who always understood him, not letting go until he’d quashed the lump in his throat and the burn in his eyes.

“You should stop, Oleg. This thing you do brings you nothing good.” As always when she mothered him, her accent thickened until she sounded more like their mother than herself.

He nodded, saying nothing, and accepted the offered tea glass. She put a plate of pirozhki down on the big round kitchen table, and they sat next to each other to share.

“Look elsewhere,” she said. “Then you can find a nice man, instead.”

Unbidden, the guitarist in the Market came vividly to mind, three-dimensional like a hologram. “Maybe so,” Oleg said, hope somehow rising up even as he thought the prospect unlikely. He repeated, “Maybe so.”

She smiled, and then they sat silent. He filled his empty stomach with pirozhkis, washed them down with hot, dark Caravan tea.

“It’s good you eat, Olejka. Your voice will fade away if you grow any thinner, and then what will we do?”

Oleg grinned as he rose to clear the table. It was a joke he’d heard at least once a week since early adolescence.

That she expected no response was evident as she switched topics without missing a beat. “If you don’t have your shopping done for Christmas, come with me to the Market tomorrow.”

Oleg heard the word Market and his pulse suddenly raced, the thought of going to the place where he’d seen the guitarist—and might see him again—sending him into a panic. He stared.

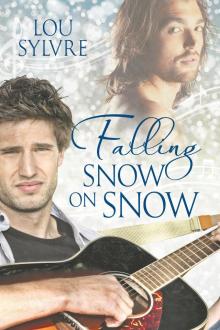

Falling Snow on Snow

Falling Snow on Snow